Not For All The Tea In China!

Learn how Robert Fortune, a classic figure of his age—a man whose scientific passions and professional ambitions aligned perfectly with imperial interests, enabling activities that would change not just gardens and botanical collections but the economic fortunes of nations.

Supporting links

1. Robert Fortune [Wikipedia]

2. East India Company [World History Encyclopedia]

3. Chinese tea culture [Wikipedia]

4. The Wardian Case: Histories Boxes for Moving Plants [Gale Academic Onefile]

5. How a Simple Box Moved the Plant Kingdom [Arboretum]

Contact That's Life, I Swear

- Visit my website: https://www.thatslifeiswear.com

- Twitter at @RedPhantom

- Bluesky at @rickbarron.bsky.social

- Email us at https://www.thatslifeiswear.com/contact/

Episode Review

- Submit on Apple Podcast

- Submit on That's Life, I Swear website

Other topics?

- Do you have topics of interest you'd like to hear for future podcasts? Please email us

Interviews

- Contact me here https://www.thatslifeiswear.com/contact/, if you wish to be a guest for a interview on a topic of interest

Listen to podcast audios

- Apple https://apple.co/3MAFxhb

- Spotify https://spoti.fi/3xCzww4

- My Website: https://bit.ly/39CE9MB

Other

- Music ...

⏱️ 15 min read

Have you ever heard the expression "not for all the tea in China?" It's an idiom that means something very valuable or priceless. It is usually used in a negative sentence to indicate that a person will not do something no matter how much money or benefit they are offered.

For another person, that idiom had a whole different meaning. I'm talking about Botanist Robert Fortune. In this story, you'll learn how Robert traveled to China and stole trade secrets of the tea industry. I guess you could say this was The Great British Tea Heist.

Welcome to That's Life, I Swear. This podcast is about life's happenings in this world that conjure up such words as intriguing, frightening, life-changing, inspiring, and more. I'm Rick Barron your host.

That said, here's the rest of this story

Robert Fortune: Tea Spy and Botanical Revolutionary - A Historical Analysis

Introduction

A lot of us like a nice cup of tea. It’s a taste that brings comfort to out taste buds. However, Behind the story of a simple cup of tea is a tale of espionage and intrigue. That cup of delicious tea has a complex, and dark history. This story of tea is a tale of politics, economics, espionage, and the drug trade.

This is the story of one of the most audacious espionage missions ever mounted: to steal the secret of tea from Imperial China.

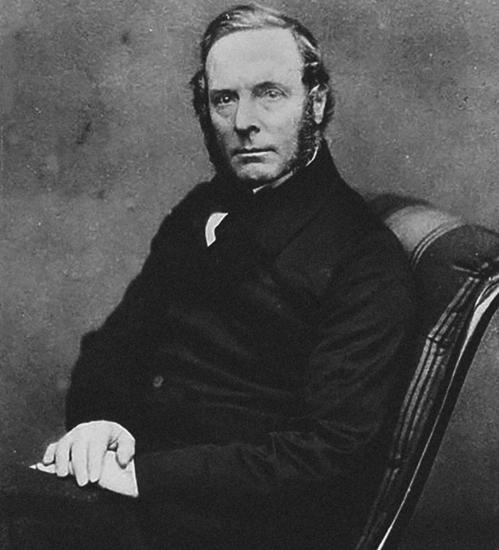

Botanist, Robert Fortune. Courtesy of The National

Few figures stand out as prominently in this story as Robert Fortune (1812-1880), whose clandestine expeditions into forbidden Chinese territories fundamentally altered the global tea trade and contributed significantly to the economic strength of the British Empire.

Fortune's exploits—donning disguises, mastering Mandarin, and penetrating restricted regions of China—read like fiction yet represent one of history's most consequential acts of industrial espionage. His story illuminates the intersection of botany, commerce, and imperial power during the Victorian era, when plants were not merely objects of scientific curiosity but critical resources of immense economic and political value.

We’ll get to Mr. Fortune in a minute. A little historical background needs to be laid out here.

The Historical Context: Tea and Empire

By the mid-19th century, tea had become deeply embedded in British culture and economics. What had begun as an exotic luxury in the 17th century had transformed into a national necessity by Fortune's time. The British Empire's relationship with China was notably unbalanced—British consumers had developed an insatiable appetite for Chinese tea, yet China showed little interest in British goods beyond silver. This trade imbalance contributed to significant economic strain and helped motivate Britain's controversial introduction of Indian opium into China, eventually leading to the Opium Wars (1839-1842 and 1856-1860).

Following the First Opium War and the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, the British gained access to five treaty ports but were still prevented from traveling into China's interior. The East India Company, though diminished in power after losing its monopoly on Chinese trade in 1833, remained a formidable economic force with expansive ambitions.

The company had an idea. They decided on a goal to enhance economic power even more: They recognized that establishing tea production in British India could dramatically shift the financial balance of power, while at the same time reducing dependence on Chinese imports and bolstering colonial profits.

Enter Robert Fortune

Robert Fortune's first journey to China was not for tea acquisition but a broader botanical collecting mission sponsored by the Horticultural Society of London. Arriving in Hong Kong in July 1843, Fortune immediately demonstrated the adaptability and determination to characterize his later missions. His journals revealed a practical man undeterred by considerable dangers, including anti-immigrant mobs, killer storms in the Yellow Sea, and pirates on the Yangtze River.

Most remarkable was Fortune's unusual approach to exploration. Rather than traveling openly as a European, he adopted Chinese dress and customs, shaving the front of his head and growing a queue (ponytail). This disguise proved surprisingly effective, allowing him access to regions otherwise closed to foreigners. His growing proficiency in Mandarin further enhanced his ability to move through Chinese society with reduced suspicion.

While this first expedition primarily focused on ornamental plants, Fortune's ability to navigate Chinese culture and geography made him an ideal candidate for a more important mission. Upon his return to England in 1846, the publication of his memoirs, "Three Years' Wanderings in the Northern Provinces of China," caught the attention of the East India Company, which recognized in Fortune the perfect agent for an audacious plan.

The Secret Mission (1848-1851): Corporate Espionage in the Service of Empire

Robert was approached by the East India Company of their idea. At first he had no interest. However, when told the compensation he would receive, he had a change of heart. Fortune's second expedition to China differed fundamentally from his first in purpose and execution. Now explicitly commissioned by the East India Company, Fortune's mission was nothing less than the

· systematic theft of tea plants

· seeds

· and the processing knowledge from China's most renowned tea-producing regions.

The mission represented an early example of targeted industrial espionage, designed to break China's monopoly on tea production.

The risks were considerable. Interior China remained officially closed to foreigners, with severe penalties for those who violated these restrictions. Despite his disguise, Fortune's six-foot height made his Scottish origins difficult to conceal. Nevertheless, in September 1848, Fortune again transformed himself into a Chinese traveler, floating on a canal outside Shanghai with his head shaved and attached a long braid of dark hair hanging onto the nape of his neck.

Fortune's subsequent journeys took him to previously unexplored regions, including the famed Wuyi Mountains in Fujian province and the Yellow Mountains (Huangshan), renowned for producing China's finest teas. His disguise, while imperfect, proved adequately convincing when combined with his servants' explanations that he was "actually the lord of a far-off nation beyond the Great Wall."

Stealing the Secrets of Tea

Fortune's intelligence-gathering at Chinese tea factories demonstrated his scientific curiosity and calculated approach to espionage. He had a servant that would precede him, creating elaborate pretexts for his visits to production facilities. Fortune observed and documented the complete tea manufacturing process inside these facilities from

· harvesting to drying

· rolling

· firing

· and fermenting

Fortune's discovery of the differing processes for green and black tea production turned out to be very valuable. European consumers had long believed that green and black teas represented different plant varieties, but Fortune discovered that the distinction lay primarily in processing methods.

· Black tea underwent an oxidation (fermentation) process that green tea did not.

· Furthermore, he found the unsettling practice of adding colorants to green tea destined for export—including poisonous compounds like Prussian blue and gypsum—to enhance its appearance for Western markets.

Fortune's meticulous notes extended beyond processing techniques to cultivation methods, soil conditions, and climate factors. He gathered this intelligence while collecting vast quantities of tea plants and seeds, carefully packed in specially designed Wardian cases (early terrarium-like containers) for the journey to India.

Perhaps most remarkably, Fortune was very astute in recruiting eight Chinese tea workers with expertise in cultivation and processing to go with him to India. These men, skilled in the carefully guarded techniques developed over centuries, would provide the intellectual property to British colonial plantations. Their recruitment represented a human dimension to Fortune's espionage, transferring plants and generational expertise from China to British territories.

The Impact: Transforming Global Tea Production

Between Fortunes trips from 1848 to 1851, he had transported over 20,000 tea plants and seedlings to the Himalayan foothills, along with his Chinese tea experts.

At first the immediate results for the processing of these various teas, had mixed results. Many plants failed to thrive in the India environment, particularly in the northwestern provinces where Fortune had first directed his shipments. This initial disappointment reflected an incomplete understanding of the specific conditions required by Chinese tea varieties.

However, the knowledge and techniques Fortune brought proved invaluable when applied to the native Assam tea variety (Camellia sinensis var. assamica), which had been discovered growing wild in northeast India in the 1830s. While botanically distinct from Chinese tea (Camellia sinensis var. sinensis), the Assam variety benefited enormously from applying Chinese processing techniques.

Within decades, India surpassed China as the world's largest tea exporter. British colonial plantations in India and later Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) dominated global tea production, fundamentally altering trade patterns established over centuries. Fortune's corporate espionage mission had essentially broken China's monopoly on tea production and transferred substantial economic power to British colonial interests.

Beyond Tea: Fortune's Botanical Legacy

While tea espionage represents Robert's most historically significant achievement, his broader contributions to botanical knowledge and Western horticulture were substantial. Across his four expeditions to East Asia (three to China and one to Japan), he introduced over 120 new plant species to Western gardens and scientific collections.

Among his most notable introductions were the kumquat, numerous chrysanthemum varieties, tree peonies, and a distinctive climbing yellow rose later named "Fortune's Double Yellow." These plants transformed European gardens and reflected the Victorian fascination with exotic flora. Fortune's later travels to Japan and Taiwan (then called Formosa) extended his contributions to include documentation of rice cultivation and sericulture (silk production).

Fortune's achievements exemplify the Victorian era's complex relationship between science, commerce, and empire. His botanical discoveries simultaneously advanced scientific knowledge enriched European aesthetic sensibilities, and served imperial economic interests.

Critical Perspectives: Evaluating Fortune's Legacy

From a contemporary perspective, Fortune's missions invite critical examination regarding the ethics of appropriation and exploitation in colonial contexts. While celebrated as enterprising and ingenious in Victorian Britain, his activities fundamentally represented the unauthorized removal of biological resources and traditional knowledge developed over centuries by Chinese cultivators.

Fortune's expedition occurred at a historical inflection point when China's traditional isolation was forcibly giving way to European intervention. The First Opium War had recently concluded, with China compelled to grant concessions to Western powers. While less overtly violent than military campaigns, Fortune's activities represented another form of exploitation enabled by imperial power. His missions occurred when China's sovereignty was increasingly compromised, and Western powers felt entitled to access Chinese resources by whatever means necessary.

Yet Robert himself appeared motivated not primarily by imperial ideology but by scientific curiosity and professional ambition. His writings reveal genuine respect for Chinese culture and landscapes, even as he systematically gathered intelligence that would undermine Chinese economic interests. This complexity makes Fortune neither a simple villain nor an uncomplicated hero but rather a figure who embodied the contradictions of his era.

Conclusion: The Tea Spy's Enduring Significance

Robert Fortune's expeditions to China represent a pivotal moment in global economic history, effectively ending a Chinese monopoly on tea production that had persisted for centuries. Through botanical knowledge, cultural adaptability, and calculated deception, Fortune facilitated a massive transfer of biological resources and traditional knowledge that would reshape global trade patterns for generations.

The ramifications extended far beyond economics. Tea plantations, with profound social and environmental consequences, became a defining feature of British colonialism in India. The plantation system established patterns of labor exploitation that would persist long after colonialism formally ended. At the same time, tea consumption patterns established during this period continue to shape cultural practices worldwide.

Fortune's story illuminates the intimate connections between botany, commerce, and imperial power during the Victorian era. Plants were never merely objects of scientific curiosity but strategic resources with immense political and economic value. Fortune's botanical espionage mission succeeded because the British Empire recognized what China had long understood: that tea represented not just a beverage but a source of wealth, power, and cultural identity.

What can we learn from this story? What's the takeaway?

In the final analysis, Robert Fortune is a classic figure of his age—a man whose scientific passions and professional ambitions aligned perfectly with imperial interests, enabling activities that would change not just gardens and botanical collections but the economic fortunes of nations.

His legacy reminds us that global history has often turned not just on battles and treaties but on the movement of plants, seeds, and the knowledge required to cultivate them.

Well, there you go, my friends; that's life, I swear

For further information regarding the material covered in this episode, I invite you to visit my website, which you can find on Apple Podcasts for show notes and the episode transcript.

As always, I thank you for the privilege of you listening and your interest.

Be sure to subscribe here or wherever you get your podcast so you don't miss an episode.

And we'll see you soon.