David Edward Byrd: Psychedelic Poster Legend

David Edward Byrd developed iconic swirling and psychedelic posters and illustrations associated with the best of the rock and theatre era.

Supporting links

1. David Edward Byrd Posters [ArtPal]

2. David Byrd Creatives [Laetro]

3. 1968 poster for The Jimi Hendrix Experience [Vintage Poster]

4. Poster Child: The Psychedelic Art & Technicolor Life of David Edward Byrd [Amazon]

5. Jolino Architectural Mosaics [Website]

Contact That's Life, I Swear

- Visit my website: https://www.thatslifeiswear.com

- Twitter at @RedPhantom

- Bluesky at @rickbarron.bsky.social

- Email us at https://www.thatslifeiswear.com/contact/

Episode Review

- Submit on Apple Podcast

- Submit on That's Life, I Swear website

Other topics?

- Do you have topics of interest you'd like to hear for future podcasts? Please email us

Interviews

- Contact me here https://www.thatslifeiswear.com/contact/, if you wish to be a guest for a interview on a topic of interest

Listen to podcast audios

- Apple https://apple.co/3MAFxhb

- Spotify https://spoti.fi/3xCzww4

- My Website: https://bit.ly/39CE9MB

Other

- Music ...

⏱️ 14 min read

Close your eyes and picture this—swirling colors, the trippy fonts, the electric energy of the late '60s and '70s. Now, imagine rock legends like Jimi Hendrix, The Rolling Stones, and The Who—framed in vibrant, mind-bending posters that defined that era.

Those posters? They came from one man: David Edward Byrd. He wasn't just an artist—he was the visual architect of a revolution. David was the man who gave rock and Broadway their most unforgettable look. He turned music into a feast for the eyes.

Welcome to That's Life, I Swear. This podcast is about life's happenings in this world that conjure up such words as intriguing, frightening, life-changing, inspiring, and more. I'm Rick Barron your host.

That said, here's the rest of this story

Legendary poster artist David Edward Byrd died at the age of 83. The creative force behind memorable artwork for Broadway productions including "Godspell," "Follies," "Jesus Christ Superstar," and "Little Shop of Horrors" passed away due to pneumonia on February 3, 2025, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. His partner, Jolino Beserra, announced the loss through a Facebook post.

What follows is a snapshot of David's life.

David Edward Byrd at home in 2010. Courtesy of Google

Born in Cleveland, Tennessee on April 4, 1941, David relocated to New York City after completing both his Bachelor's and Master's degrees in Fine Arts at Carnegie-Mellon University during the 1960s, determined to establish himself in the art world.

In 1967, David joined Fantasy Unlimited, a curious blend of hippie commune and entrepreneurial venture based on a farm in Port Jervis, N.Y. This collective of young artists specialized in creating elaborate multimedia light shows featuring pulsating colors, hand-crafted animations, bubbles, and strobe effects for dance events and corporate functions. As collective member Nina Berson explained, "We were trying to introduce sensual-awareness experiences into corporate environments."

Despite his classical training at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), where he earned an MFA in stone lithography and studied masters like Caravaggio, Gauguin, and Bacon, David was drawn to this unconventional artistic path.

His participation came after struggling post-graduation—he once quipped, "The only job I could get was washing underwear in an Armenian laundry." The opportunity to join Fantasy Unlimited came through his former college roommate, a founding member who extended an invitation during David's professional difficulties.

Around this time, another Carnegie graduate, Joshua White, had established a celebrated light show collective of his own. In early 1968, White convinced influential promoter Bill Graham to hire David for poster design work at Graham's newly opened Fillmore East venue in New York City. The assignment was to create promotional material for an upcoming performance featuring The Joshua Light Show alongside musical acts Traffic, Iron Butterfly, and Blue Cheer.

Though David had no previous experience with concert poster design, he approached the task with a clear philosophy. He believed a good poster "should be calling to you across the street, luring you in, or punching you in the face," as he would later describe. The result was a visually commanding image featuring four Native American men gazing directly upward at the viewer, set against a dramatic tunnel of psychedelic coloration in vibrant pink, purple, and orange hues.

The poster profoundly impressed Graham, who continued commissioning David's work until the Fillmore East's closure in 1971. This initial success launched David into a prolific career spanning the subsequent decade. His diverse and luminous artistic output—encompassing rock concert promotions, Broadway show materials, book jackets, and album covers—would ultimately help define the visual aesthetic of a generation.

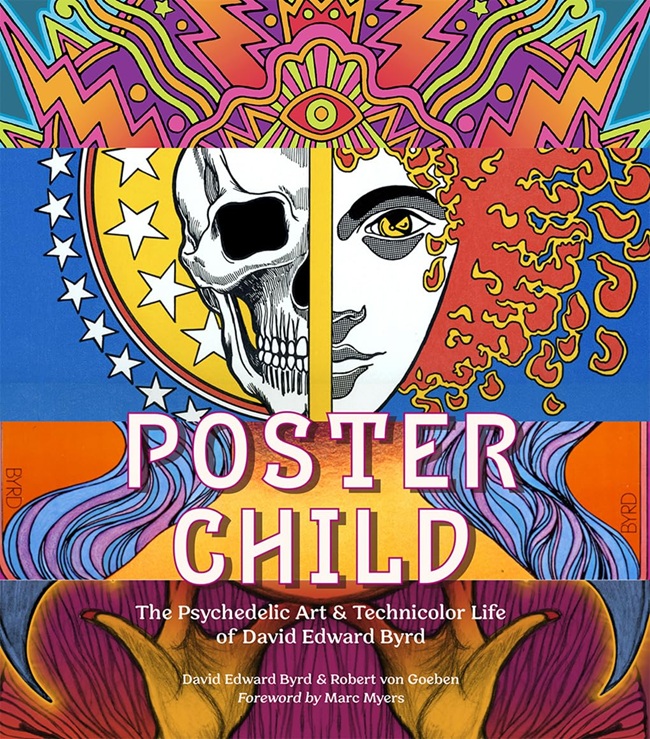

The Poster Child book by David Edward Byrd and Robert von Goeben. Courtesy of Amazon

Within this striking design lay calculated artistic choices. In his 2023 book collaboration with Robert von Goeben titled "Poster Child," David revealed the intentional science behind his work. The deliberately clashing color combinations were engineered to create visual disruption, producing a strobe-like effect. As he described it, "Your rods and cones struggle to identify the colors, creating a vibrating sensation in your retina. Yet your brain persists in trying to isolate a single color."

The Hendrix Legacy

Perhaps David's most iconic creation was his 1968 poster for The Jimi Hendrix Experience. In this remarkable work, he reimagined Hendrix's signature Afro as an intricate mosaic of tiny, vibrant circles—each painstakingly hand-drawn using a drop bow compass—that seamlessly blended into his bandmates' hair. Today, these original posters grace distinguished institutions including MoMA and the Louvre, with some commanding up to $12,000 in online auctions.

Ironically, David himself had to purchase one of his own creations later in life. He viewed posters as temporary objects—designed to be torn down or covered once their purpose was served—and consequently preserved little of his early portfolio.

His remarkable talent lay in transforming the temporary into the timeless.

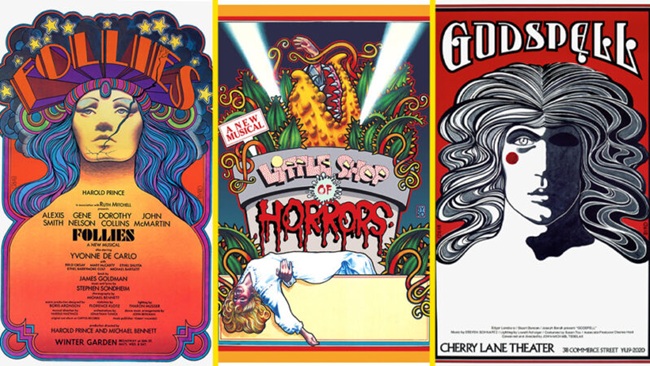

Various posters by David Edward Byrd. Courtesy of Playbill

David's contributions to counterculture imagery were deeply rooted in his extensive knowledge of art history. His Rolling Stones tour poster drew inspiration from Eadweard Muybridge's

19th-century motion photography. For Jefferson Airplane, he employed Egyptian artistic conventions, while his work for The Who's "Tommy" incorporated elements reminiscent of Busby Berkeley's elaborate choreography.

When asked to create a poster for a 1969 event called the "Aquarian Exposition," David drew immediate inspiration from the French Academic tradition. Specifically, he referenced Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres's 1856 work "La Source," which depicts a naked female figure holding a water vessel. Though David developed a design based on this classical image, fate intervened—the festival (which would later become famous as Woodstock) unexpectedly changed venues, and organizers couldn't reach David, who was traveling abroad, for necessary revisions. Consequently, his artwork went unused.

What distinguished David was his remarkable creative efficiency and unwavering commitment. He conceived complex artistic concepts rapidly, embraced them wholeheartedly, and pursued their execution with determination. Joshua White noted David’s exceptional work ethic: "I never saw him sitting there muttering, 'What am I gonna do? What am I gonna do?'" Unlike many contemporaries, David rejected the notion that commercial projects compromised artistic integrity. As he candidly told Vanity Fair, "It's all art. After all, John Singer Sargent had to please the Astors. It's all a racket, kiddo."

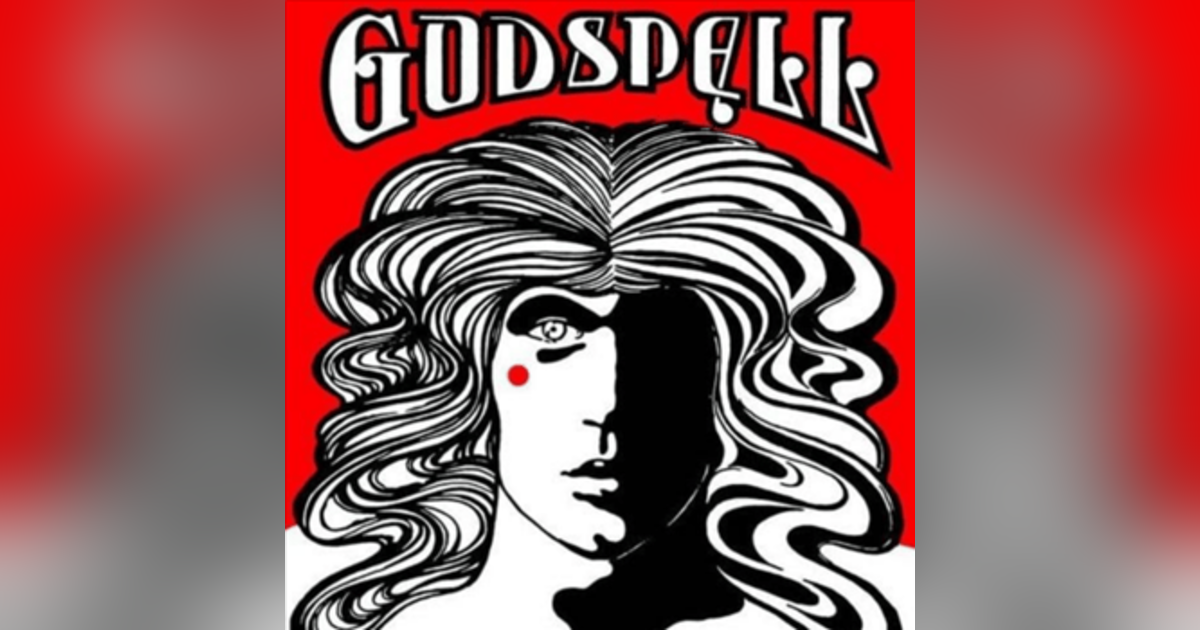

For some devotees, though, David left his most indelible impression on Broadway, designing some of theater’s most influential and best-remembered posters and logos.

When David designed a poster for the Sondheim musical "Follies" in 1971, he created something revolutionary. His image featured a showgirl represented as a fractured marble sculpture, with the production's title bursting from her spectacular, subtly psychedelic headpiece.

According to renowned Broadway poster designer Frank "Fraver" Verlizzo, this creation "transformed perceptions of theater posters as artistic expressions. Previously, most consisted merely of celebrity photographs paired with stylized lettering." Following this breakthrough, David continued his theatrical innovation with another influential design for "Godspell."

Though David found creating for Broadway invigorating, he acknowledged to Playbill that it demanded more intensive preparation than his rock concert work. "With rock posters, I could draw virtually anything—even something as bizarre as ducks consuming a lizard. As long as it had psychedelic appeal, the specific imagery wasn't crucial," he explained. "Theater posters, however, required actual script analysis."

For the stage, Byrd additionally designed posters for Little Shop of Horrors, The Robber Bridegroom, The Grand Tour, The Survival of St. Joan, and Jesus Christ Superstar.

Early Struggles

David Edward Byrd entered the world, as an only child. At age 3, while David's father Willis served in World War II, his mother Veda made the decision to place him in foster

care—a strategic move to pursue a more financially advantageous marriage.

Her plan succeeded within approximately two years. After wedding Albree Miller, an executive with Howard Johnson's, Veda reclaimed her son. The family relocated to Miller's pristinely designed Miami Beach residence—a Midcentury Modern showcase featuring luxurious carpeting and vibrant pastel décor that neighboring residents nicknamed "The House of Tomorrow."

Despite the opulent surroundings, David’s youth was marked by profound unhappiness. He found himself disturbed by his parents' chaotic lifestyle. In his published memoirs, he describes scenes of intoxicated guests at parties impulsively diving from balconies into the swimming pool while fully clothed. Meanwhile, young David—dressed formally in a navy suit with red bow tie—was tasked with mixing gin slings as a child bartender.

Art eventually became David's guiding passion and defining force. After completing high school in 1959, he took employment at a Pittsburgh steel mill to fund his studies at Carnegie, as his stepfather refused financial support for what he considered a worthless degree.

During his first Thanksgiving break, tragedy struck when David and a friend's vehicle careened off the road. Regaining consciousness, David discovered people lifting the car off him. The accident fractured his pelvis, tailbone, and two neck vertebrae, necessitating months of rehabilitation in a Pennsylvania hospital. His parents visited just once—intoxicated and en route to Paris—during his six-month recovery. Later, in 1962, David would discover his mother deceased beside vodka and sleeping pills.

The accident aftermath led David into painkiller dependency, depression, and anorexia. "I was just angry, angry, angry," he confessed in "Poster Child." Upon returning to art school, he subsisted on water and Wonder Bread, eventually requiring brief commitment to a psychiatric facility.

By 1980, despite professional success in New York, David's substance issues expanded to include heroin and opium. "I didn't recognize my lack of control then," he admitted. Seeking a fresh start, he relocated to Los Angeles for work on Van Halen's "Fair Warning" tour—a band he "never even heard of." He departed New York with only his toothbrush, portfolio, and his entire $548 net worth.

Though David secured other California commissions, including KISS band portraits, his New York reputation and artistic approach didn't immediately resonate on the West Coast. He accepted modest assignments illustrating insurance advertisements and packaging instructions, including directions for "How to Heat an Egg Roll."

At first, David hated Los Angeles. "God, you can hear the f—ing plants grow," he once wrote. But everything changed in late 1981 when he met Jolino Beserra, a young mosaic artist. With him, he found a newfound appreciation for the city—and life itself—embracing both with a calm and joy that had previously eluded him. Their bond endured, and after decades together, they married in 2013, ultimately sharing 43 years as partners.

David's career took a pivotal turn in 1991 when he was brought on to build an in-house creative services department at Warner Bros. For the next 11 years, he lent his vision to a wide range of projects, designing everything from Looney Tunes stamps for the U.S. Postal Service to the popular TV show, "Friends" merchandise and style guides for the early "Harry Potter" films.

David thrived in his work. Reflecting on his time at Warner Bros., he told Be Inkandescent magazine that it was the best education he ever received—more intense and inspiring than art school. Immersed in hands-on artwork for eight to ten hours a day, he was constantly surrounded by other artists and mastering computer illustration software for the first time.

Some might have dismissed the job as trivial. "Someone could be stuck up about it and say, 'Why did you love it? You were drawing Tweety Bird?'” said Von Goeben. “But as David would tell me, ‘What’s not to love? I get to paint all day.’”

Even after leaving Warner Bros., David never stopped creating. As Beserra recalled, he kept busy with freelance gigs, but he also poured his talent into pro bono projects—designing posters for charity events, struggling small theaters, and T-shirts for animal rescues. Making art wasn’t just his job; it was his refuge. “When he could just get lost in the work, he was happiest,” Beserra said. “What saved him, always, was getting out of his own head.”

What can we learn from this story? What's the takeaway?

I came across a notable quote from David Byrd, that I think summarizes his life. And I quote:

“Unfortunately, I gave so many posters away like a drunken sailor. To me they were disposable items. You just did it for this moment and who knew that 50 years later you would rue the day that you gave them all away or only saved five. That’s just the way I was, I didn’t plan for the future. I didn’t expect to live this long. Good god.” End quote

Well, there you go, my friends; that's life, I swear

For further information regarding the material covered in this episode, I invite you to visit my website, which you can find on Apple Podcasts for show notes and the episode transcript.

As always, I thank you for the privilege of you listening and your interest.

Be sure to subscribe here or wherever you get your podcast so you don't miss an episode.

And we’ll see you soon.